Chapter 10 of the book ‘Scared To Death’ provides essential background reading for anyone seeking to understand how we have arrived at the authoritarian speed enforcement regime that we now have in the UK.

SPOILER ALERT: The regime is based on fear, and involves a ‘dodgy dossier’ promoted by the Department for Transport and an infamous technocrat named Tony Blair!

The chapter traces the origins of speed limits back to early 20th-century Britain, where initial restrictions like the 20 mph limit in 1903 arose from concerns over automobile dangers. It argues that the modern “speed kills” scare gained traction in the late 20th century, particularly with the introduction of speed cameras in the 1990s. Booker and North contend that this shift was fuelled by a coalition of safety campaigners, politicians, and media outlets who latched onto the simplistic slogan “speed kills,” despite evidence suggesting a more complex relationship between speed and road fatalities.

They highlight how statistical data was selectively used to exaggerate speed’s role in accidents. For instance, while government reports in the 1980s and 1990s claimed speed was a factor in a third of crashes, the authors argue this figure was inflated by including cases where speed was incidental rather than causal (e.g., minor speeding in already dangerous situations like drunk driving). They contrast this with studies showing that only 5-7% of accidents were directly attributable to excessive speed, suggesting the scare was disproportionate to the reality.

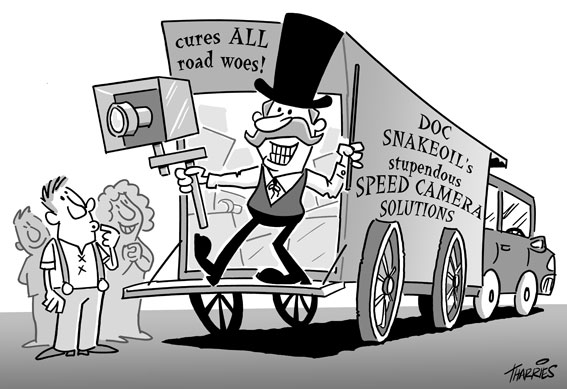

The chapter critiques the rollout of speed cameras in Britain, portraying them as a revenue-generating tool masquerading as a safety measure. The authors cite the 1991 introduction of cameras and the subsequent political push by Tony Blair who championed their expansion. They argue that the focus on enforcement—fining drivers for minor infractions—diverted attention from more significant causes of road deaths, such as poor road design, driver inattention, or intoxication.

A 2003 Department for Transport study is referenced, showing that cameras reduced accidents at specific sites but had little impact on overall fatality rates, with some evidence suggesting drivers slowed excessively at camera locations only to speed up elsewhere, negating safety gains.

Image Credit: Paul Smith. Safepeed http://www.safespeed.org.uk/

Booker and North also explore the unintended consequences of this scare. They assert that the obsession with speed limits and cameras frustrated drivers, eroded public trust in safety policies, and even cost lives by misdirecting resources. For example, they claim that emergency response times may have been hampered by overly strict speed enforcement on police and ambulance drivers.

The chapter contrasts Britain’s approach with countries like Germany, where sections of the Autobahn lack speed limits yet maintain lower fatality rates, suggesting that road engineering and driver behaviour are more critical than blanket speed restrictions.

Singled out in the Chapter is “speed kills” fanatic Richard Brunstrom, the Chief Constable of North Wales Police who attempted to silence Safespeed’s Paul Smith when it became known that dozens of serving police officers had contacted Smith to express concern at the way reliance on speed cameras had become a substitute for a road safety policy which, until ten years previously, had been internationallty acclaimed as the most successful in the world.

In September 2006 the DfT finally conceded one of the central points which Paul Smith had been arguing for five years: that only 5% of road accidents were caused by drivers who were breaking the speed limit. In the Daily Telegraph, Smith was quoted as saying “the government’s case for continuing to install cameras has been destroyed”.

The Guardian’s environmental columnist George Monbiot is also mentioned in this Chapter having published a ferociuos attack on people like Smith who dared to challenge the government’s policy. He painted Smith as a member of the “boy racers club” and one of the anti-social bastards who believe they should be allowed to do whatever they want regardless of the consequencies.

What Monbiot conveniently failed to acknowledge was that, far from arguing for a free for all on the roads, Smith’s prime concern was to return to a road safety policy that worked, based not on some abstract dogma but regulated by the methods which had formerly given Britain’s traffic police such an enviable reputation.

Ultimately, the authors frame the “speed kills” phenomenon as a scare that followed their recurring pattern: a kernel of truth (speed can contribute to accidents) was exaggerated by “pushers” (safety advocates and media), leading to a disproportionate response (ubiquitous cameras and fines) that ignored broader context and evidence.

They argue this not only failed to deliver promised safety improvements but also imposed significant economic and social costs, fitting their broader thesis that fear-driven policies often do more harm than good.

Footnote I bought my copy of ‘Scared To Death – From BSE To Global Warming: Why Scares are Costing Us The Earth’ from second hand bookseller World of Book for a mere £3.50 postage free) I then sought permission from the publisher to post a reprint of the full chapter here but their fee was prohibitive, hence my summary.